The Meaning of Salzburg – Kugeln, Kitsch or Kultur?

August 27, 2016

Well, it’s time, I guess. Time to dust off this blog after a long while away. As I write I am rolling westwards back to France through the Austrian and Swiss Alps after a brief but intense visit to what you might call ‘Classical Music HQ’, that most outrageously beautiful and thoroughly ambiguous of European cities – Salzburg in all its disconcerting glory at the back end of the 2016 Festival, where ‘culture’ is spelt not only a capital K but also capitals U, L, T, U and R. If you don’t pen something about Salzburg on a music blog, then you’re probably not going to write about anything.

In case you haven’t been, all (well, perhaps almost all) of your clichés about Salzburg have at least a grain of truth to them. The Old Town, where you are more likely to meet visitors from St Petersburg and Shanghai toting selfie-sticks than Austrians wearing Lederhosen and Dirndl, is a tourist trap to beat all tourist traps, a heady mix of shameless pseudo-Mozart-Kitsch and high-end international fashion à la Prada. If you aren’t careful, you are likely to find yourself regretting the good euros with which you were persuaded to part in order to hear sub-standard versions of Wolfgang Amadeus’s Requiem sung by well-meaning but vocally-challenged choirs from Oklahoma or operatic wannabees performing your favourite tunes from Die Zauberflöte accompanied by beatbox or didgeridoo. And yes, although I didn’t actually see anyone boarding the Sound of Music Bus, walking through Salzburg’s wonderfully narrow streets is like being in a film set.

Nonetheless, even though peeling away the layers of the city in order to find what is real is no easy matter (I was witness to an involved conversation between locals as to what constitutes the difference between an ‘original’ and an ‘authentic’ chocolate Mozartkugel), there is no denying it: Salzburg is still ravishingly beautiful. Walking on a summer evening through the Mirabell Gardens or along the banks of the Salzach river, there is a palpable sense of idyllic repose which cannot be dismissed as merely manufactured, in this place where classical music somehow improbably remains king and the bicycle is the preferred means of locomotion. Even the most anti-Romantic observer might just find it within themselves not to sneer inwardly at the over-dressed festivaleers who have come from far away to fulfill the Dream Of A Lifetime by attending Gounod’s Faust in the Grosses Festspielhaus.

Salzburg has for a long time been a combination of transcendent beauty – not least because of its peerless Alpine setting – and relentless human ambition. That didn’t begin with the creation of the Salzburg Festival, even if the careers of those all-too-flawed geniuses Richard Strauss and Herbert von Karajan (the latter labelled with laudable transparency ‘The Last Absolutist Ruler’ in the history section of the official Festival website) perhaps demonstrate that juxtaposition more famously than any other classical musicians of the twentieth century. You can already sense the ambiguous relationship between aesthetics, sprituality and power politics in the magnificent Baroque Cathedral where I had the privilege of giving an organ recital – the purpose of my visit to Salzburg – yesterday. On one hand, the sight that greets an organist climbing the steps in order to practise on the sumptuous Metzler organ in the loft at the west end of the Cathedral is somewhat overwhelming, not only on a visual level but because of the historical associations of this incomparable space. For a church musician whose whole education is based on reverence for the musical greats of past centuries, this place – like the Thomaskirche in Leipzig, San Marco in Venice or La Trinité in Paris – is hallowed ground in more than one sense. If you do not experience a feeling of spiritual elevation and a stirring of your musical blood here, then you probably need help. Walk down the steps to the Cathedral Museum on the other side of the loft, however, and the reverse side of the medal becomes troublingly apparent in the form of a display of the dazzlingly excessive liturgical trappings of the Baroque archbishop-princes who made Salzburg their fiefdom. If you don’t find yourself asking the question of what precisely this unapologetic show of clerical-political vainglory has to do with the Carpenter of Nazareth born in a stable and mercilessly executed at Jerusalem’s town dump, then you definitely need help.

It is this ambiguous relation between the Sacred and the brazenly Secular, the Church and the World, which arguably lies at the heart of Salzburg’s split personality. Start practising on the gallery organ during the daytime and you will experience this ambiguity directly, but be forewarned: you had better abandon lofty notions of communing in blessed artistic solitude with the harmony of the spheres, as the reality is that you are more likely to be surrounded by curious tourists at arm’s distance from the organ console, meaning that your wrong pedal notes stand a fair chance of appearing on YouTube even before you’ve reached your final cadence. A softly-spoken but wise cathedral musician informed me that, much to my astonishment and his chagrin, tourists are even allowed to circulate freely in the gallery during the liturgy (of which many of them naturally have no concept whatever)! I leave it up to the reader whether this deconstruction of the boundary between the sacred and the profane should be interpreted as a praiseworthy – if highly unusual – form of ‘openness to the world’ or simply an act of capitulation to the prosaic logic of market forces. All I would say is that the musician in question saw it all as the sign of a dying culture (sterbende Kultur..), although at the same time he did emphasize that, thankfully, Salzburg Cathedral is still a church. If that might seem like stating the obvious, his words gave me pause for thought as the previous day I had seen a Facebook post by the justly famed improviser David Briggs concerning his concert on another Metzler organ in the Grote Kerk in The Hague – a church which despite retaining its former name is now a museum.

A stroll through Salzburg’s Old Town with its many functioning churches serves as a welcome reminder that, for all the commercialism and the influx of Big Money of sometimes questionable provenance, a persistent undercurrent of devout, mystical Christian faith remains present in the city. In Salzburg you can still find wayside shrines in public places with figures of the crucified Christ that would be unthinkable in The Hague, and although the chocolate-box image of religious life immortalized by Julie Andrews and co. in The Sound of Music has precious little to do with reality, the fact remains that bell-drenched Salzburg still bears the profound imprint of its monastic communities. An obvious example are the Capucins on the Kapuzinerberg that dominates the bank opposite the Cathedral, where a steep but brief climb away from the boutiques of the Linzer Gasse takes you up to a world of Franciscan spirituality reminiscent of other mountain-top sanctuaries such as La Verna, where Il Poverello received the stigmata.

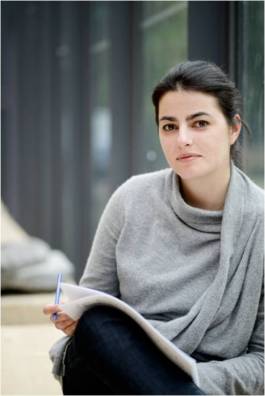

So what do you play in the Salzburger Dom knowing that your audience has probably been pestered with fake-Mozart all the way to the Cathedral steps? Well, J.S. Bach, of course (while remembering Karl Barth’s famous quip that in God’s presence the angels only play Bach, but in private they play Mozart and God listens with special pleasure) and my own small tribute to the master’s O Mensch bewein’, but I decided to intersperse works of the Thomaskantor with two pieces whose purity and innocence I felt would provide a temporary antidote to the calculated schmaltz-mongering outside the walls. One was Arvo Pärt’s utterly stripped-down Pari Intervallo, both starkly penitential and yet humbly confident, accompanied by the Pauline text ‘in life or in death, we belong to the Lord’ (Romans 14:8). The other was the 2010 Diptych by the Anglo-Bulgarian composer Dobrinka Tabakova (b. 1980) whose output I have only recently discovered. She has come to international attention of late (my friend John Metcalf for example programmed a hatful of her works at last year’s Vale of Glamorgan Festival) thanks notably to some stunning recordings of her radiant string music displaying a genuine, unaffected melodic gift and a refreshing lack of concern for alignment with any compositional school or trying to second-guess the listener’s expectation. Basically, with each piece that I’ve heard by Dobrinka Tabakova, my impression is that she simply writes what she feels she has to write and ignores the rest (in this respect her approach for me somewhat resembles that of Gavin Bryars or the Latvia Peteris Vasks). This is music which doesn’t pretend to be anything, but simply is, without any sense of embarrassment at its own beauty. Tabakova’s organ Diptych is no exception, particularly in the highly original opening ‘Pastoral Prelude’ which demonstrates her typical and intriguing synthesis of Southeast European and British influences in transforming the organ into what she describes in the score as ‘something resembling a giant bagpipe and flute’. This is followed by a slow-moving, pan-diatonic Chorale which builds to a truly ecstatic culmination from the simplest of materials (the closest parallel that comes to my mind, though probably an unconscious one from the composer’s standpoint, is the modal writing of Jehan Alain (1911-1940) back in the 1930s which could be termed pre-minimal). Spatially rather than temporally conceived, the Chorale found in the vast nave of the Cathedral a perfect environment in which to resound.

So what do you play in the Salzburger Dom knowing that your audience has probably been pestered with fake-Mozart all the way to the Cathedral steps? Well, J.S. Bach, of course (while remembering Karl Barth’s famous quip that in God’s presence the angels only play Bach, but in private they play Mozart and God listens with special pleasure) and my own small tribute to the master’s O Mensch bewein’, but I decided to intersperse works of the Thomaskantor with two pieces whose purity and innocence I felt would provide a temporary antidote to the calculated schmaltz-mongering outside the walls. One was Arvo Pärt’s utterly stripped-down Pari Intervallo, both starkly penitential and yet humbly confident, accompanied by the Pauline text ‘in life or in death, we belong to the Lord’ (Romans 14:8). The other was the 2010 Diptych by the Anglo-Bulgarian composer Dobrinka Tabakova (b. 1980) whose output I have only recently discovered. She has come to international attention of late (my friend John Metcalf for example programmed a hatful of her works at last year’s Vale of Glamorgan Festival) thanks notably to some stunning recordings of her radiant string music displaying a genuine, unaffected melodic gift and a refreshing lack of concern for alignment with any compositional school or trying to second-guess the listener’s expectation. Basically, with each piece that I’ve heard by Dobrinka Tabakova, my impression is that she simply writes what she feels she has to write and ignores the rest (in this respect her approach for me somewhat resembles that of Gavin Bryars or the Latvia Peteris Vasks). This is music which doesn’t pretend to be anything, but simply is, without any sense of embarrassment at its own beauty. Tabakova’s organ Diptych is no exception, particularly in the highly original opening ‘Pastoral Prelude’ which demonstrates her typical and intriguing synthesis of Southeast European and British influences in transforming the organ into what she describes in the score as ‘something resembling a giant bagpipe and flute’. This is followed by a slow-moving, pan-diatonic Chorale which builds to a truly ecstatic culmination from the simplest of materials (the closest parallel that comes to my mind, though probably an unconscious one from the composer’s standpoint, is the modal writing of Jehan Alain (1911-1940) back in the 1930s which could be termed pre-minimal). Spatially rather than temporally conceived, the Chorale found in the vast nave of the Cathedral a perfect environment in which to resound.

Dobrinka Tabakova (photo:Dobrinka Com)

Leaving the Old Town for the station this morning, my feeling was that I am still no closer than when I arrived to solving the riddle that is Salzburg and its relationship to an outside world increasingly marked by conflict and chaos. Indeed, that outside world is rapidly advancing on the sacred halls of High Culture; Salzburg has after all found itself over the last couple of years on the ‘refugee/migrant highway’ leading from Budapest and the Balkans to Munich and beyond, with the associated challenges and consequences. The question is inescapable: as the operagoers fan themselves in front of the Festspielhaus, more modest tourists contentedly munch their bruschetta in the restaurants and children play in the improvised fountains on the Old Town pavements to the accompaniment of the sounds of a ‘come-and-sing’ Mozart Lacrimosa in the Cathedral, is this ultimately all simply mindless escapism, more highbrow and yet only slightly more in touch with reality than dulling one’s intellect by chasing Pokémon-Go monsters?

Although I naturally don’t have a definitive answer, I am inclined to suggest that it largely depends whether we still have the sensitivity to treat the monuments of the past as more than simply beautiful ‘cultural artefacts’ or museum-pieces. In the case of music, can we cut through the numbing effect of attributing canonical status to ‘masterworks’ in order to recover the frequently timeless message they were originally intended both to convey and embody? If we can muster up just enough intensity to hear the Dies Irae from the Requiems of Mozart, Verdi or Dvorak, or Bach’s Erbarme dich on this level, listening according to what I referred to on this blog’s very first post as the ‘hermeneutics of danger‘ (to use a term of theologian Johann Baptist Metz) then we might just yet perhaps find in what is left of Kultur a source of inner strength, one that goes beyond Kitsch and Kugeln and has relevance for the facing of contemporary crises. That still has meaning in the world of Brexit and Donald Trump, ISIS and the Boko Haram. But if not, if a once vital culture is reduced to an albeit consoling repetition of ‘our favourite things’ on the part of a moneyed elite (to which by comparison with the refugees from Syria and elsewhere most of us de facto belong, regardless of whether we are inside the Festspielhaus or eating ice-cream outside), then I suspect that we risk facing a re-run of what followed ‘the last Golden Days of the Thirties’, as that film puts it in its opening line.

Outside Salzburg Cathedral on my way to practise I saw a guitarist soothing the crowds with his version of Sting’s Every breath you take. The thought of the Cathedral’s Doors of Mercy reminds me to be charitable, so I won’t begrudge him or his listeners a few moments of what I might otherwise be tempted to describe as Romanticism for baby-boomers. But what would their reaction be, I wonder, if our would-be troubadour instead fired up his amplifier to some words from Bob Dylan’s All Along the Watchtower that I for some strange reason found running through my mind as I made my way back to the Hauptbahnhof past the wandering street people, Roma and refugees?:

‘Outside in the distance a wildcat did growl. Two riders were approaching, the wind began to howl.’