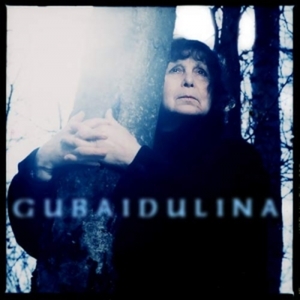

In the third part of this series on Sofia Gubaidulina we will be taking a closer look at her St John Passion, the work that she herself regards as her opus summum (together with its companion pîece St John Easter), and on which I already touched in the post ‘Expressing the Inexpressible’ when discussing the Passion 2000 project launched by Helmuth Rilling and the Stuttgart Bach Academy.

There can be no doubting the centrality of the Cross in Gubaidulina’s output; it is apparent that for her it constitutes more than a symbol recalling the death of the historical Jesus, being rather a disclosure of the fundamental nature of reality linking life and death, heaven and earth. At the heart of her theology of the Cross is kenosis, the notion of self-emptying, which can be related to what Gerald McBurney and Dominic Gill have termed her ‘Poor Music’, Gubaidulina’s habit of composing with what might appear the most meagre material, ‘the way she generates enormous energy and concentration using the frailest wisps of sound, breath-like sighs and moans, scraps of Russian Orthodox chant, gigantic but extremely simple unisons, shudders and tremblings like the merest moments of tension from a film score, the simplest common chords.‘[1] This approach is philosophically very similar to the ‘voluntary poverty’ of Arvo Pärt’s radically stripped-down tintinnabuli works or Silvestrov’s ‘voluntary disarmament'[2] in pieces such as as his Silent Songs; with all three figures, despite the stylistic differences between them, there seems to be a shared appreciation that truth and authentic personhood in art as in life can only be attained by dying to self.

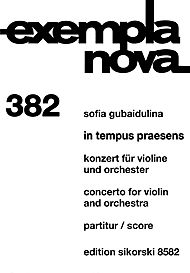

This is apparent in the work that first brought Gubaidulina to attention in the West, the remarkable violin concerto Offertorium, written for Gidon Kremer; her comments on the genesis of the piece indicate the way in which hearing Kremer’s violin playing immediately suggested to her that artistic ‘self-sacrifice’, an ek-static giving of oneself entirely to the music, acts as a pointer to the self-giving character of God:

“In this union of the tip of the finger and the resonating string lies the total surrender of the self to the one. And I began to understand that Kremer’s theme is sacrifice – the musician’s sacrifice of himself in self-surrender to the tone.”[3]

This connection between artistic self-forgetting and Divine kenosis can be found in the writings of the Russian religious philosopher Nikolai Berdyaev (1874-1948), an author whose influence on Gubaidulina would merit an extended post in itself. For Berdyaev, ‘in his creative work the artist forgets about himself, about his own personality, and renounces hmself.'[4] He asserts that although creative activity may appear individualistic, and certainly does assert the priority of the creative ‘subject’ over the ‘object’, at another level it consists in going outside oneself:

‘it strikes at the root of the egocentric, for it is eminently a movement of self-transcendence, reaching out to that which is higher than oneself. Creative experience is not characterized by absorption in one’s own perfection or imperfection: it makes for the transfiguration of man and of the world; it foreshadows a new Heaven and a new Earth which are to be prepared at once by God and man.'[5]

In Offertorium this theme of self-sacrifice is played out on a number of inter-connected levels, as the composer comments: “The sacrificial offering of Christ’s crucifixion … God’s offering as He created the world [6] … The offering of the artist, the performing violinist … The composer’s offering”.[7] Musically this is embodied by Gubaidulina’s use of the ‘royal theme’ from Bach’s Musikalische Opfer, which ‘sacrifices itself’ during the composition as notes are successively taken away from its beginning and end during a series of variations, until only a single note is left (“you cannot be reborn until you have died”[8]).In the final lyrical Chorale, which Gubaidulina terms ‘Transfiguration’, the theme is recomposed, but in retrograde form, (“the first shall be last, and the last shall be first”[9]) as a symbolization of the life of the Resurrection in which there is both continuity with earthly existence and a profound discontinuity such that “nobody can recognize it”[10].

In Offertorium this theme of self-sacrifice is played out on a number of inter-connected levels, as the composer comments: “The sacrificial offering of Christ’s crucifixion … God’s offering as He created the world [6] … The offering of the artist, the performing violinist … The composer’s offering”.[7] Musically this is embodied by Gubaidulina’s use of the ‘royal theme’ from Bach’s Musikalische Opfer, which ‘sacrifices itself’ during the composition as notes are successively taken away from its beginning and end during a series of variations, until only a single note is left (“you cannot be reborn until you have died”[8]).In the final lyrical Chorale, which Gubaidulina terms ‘Transfiguration’, the theme is recomposed, but in retrograde form, (“the first shall be last, and the last shall be first”[9]) as a symbolization of the life of the Resurrection in which there is both continuity with earthly existence and a profound discontinuity such that “nobody can recognize it”[10].

Gubaidulina’s St John Passion represents the consummation of this line of kenotic musical and theological thought as set out in In Croce, Offertorium and her powerful and disturbing Seven Words of Christ on the Cross for Cello, Bayan and Strings of 1982. The Cross symbolizes the intersection of the two dimensions of existence – ‘horizontal’ and ‘vertical’, the meeting of human history and an invisible, eternal divine realm. Textually this is reflected in the Passion in the interweaving of the narrative of John’s Gospel with passages from the Book of Revelation. Gubaidulina had already made such a connection in Offertorium, whose second section is devoted to images of the Cross and the Last Judgment, but in the case of the St John Passion and St John Easter the reference is no longer simply episodic, forming the governing structural principle of the piece as a whole:

‘John’s visions run vertically, as if time progresses in another direction. So I portray the gospel story as a horizontal timeline, and John’s revelations as vertical. I imagine that these two timelines create a cross'[11]

The composer claimed that this combination of the vertical and horizontal has precedents in visual art, having been been inspired by Giotto’s frescoes, including both Passion scenes and a depiction of the final judgment, in the Capella degli Scrovegni in Padua, which she saw in 1997:

“All I had to do in music was what had been done often and long before me in architecture and fresco painting. In my own work I have also tried to join those two texts in such a way that the two accounts, while always retaining their identity, cross each other – events on earth that take place in time (the Passion) and events in heaven that unfold out of time (the Apocalypse)”[12]

These dimensions are united by the Word who is God (John 1:1), whose death transforms the kingdom of the world into the kingdom of Christ (Revelation 11:15, quoted in section 9, ‘A Woman Clothed with the Sun’) and makes possible the outpouring of the Spirit (as the bass soloist narrates the piercing of Jesus’s side with a spear in section 10, ‘Entombment’, resulting in the flow of blood and water, the choir sings ‘He is the one who baptizes with the Holy Spirit’ (John 1:33)). This emphasis on the coming of the Spirit as the one who effects the transfiguration of the world is of course a particular focus of Eastern Orthodox theology, which has always tended to view the Cross and the Incarnation more generally in ontological terms rather than ‘forensically’ as a mechanism for the forgiveness of sins.[13] What is primarily at stake here is the defeating of death and overcoming the barrier between the creator and what is created, so that the creation can be filled with the Divine life.

The in-breaking of the ‘vertical’ dimension of eternity into time implies a drastic revision of the relationship between past, present and future, as Gubaidulina seems to suggest by her superimposition of passages from the Apocalypse and from the Passion narrative. Indeed, she sees the goal of the act of composing as the awakening of the listener to a different sense of time which remains dormant in daily life:

“In my opinion, the most important aim of a work of art is the transformation of time […] “Mankind has this other time – the time of the lingering of the soul in the spiritual realm – within himself. But this can be suppressed through our everyday experience of time.”[14]

Comments by Gubaidulina explaining her vision of the Eucharist perhaps provide a clue to the ‘liturgical’ manner in which she perceives this ‘hour of the soul’ (employing the title of her setting of a poem by Marina Tsvetaeva); in contrast to views of the Eucharist as simply remembrance of Christ’s sacrificial act, her understanding is more dynamic:

‘in the Orthodox Church the believer, in enacting the epiklesis, invokes the Holy Spirit to come and to transform in actuality the bread and the wine into Christ’s blood and body. […] And at the moment when the bread is broken, he actually experiences Christ’s death as if it were his own death, in order then to undergo true resurrection, the transformation of his human essence’ [15]

What we have in the simultaneity of Cross and Judgment in the Passion is effectively a Eucharistic conception of time writ large; as the pre-eminent Greek theologian John Zizioulas memorably puts it, working like Gubaidulina from the perspective of John’s Gospel:

‘What we experience in the divine Eucharist is the end times making itself present to us now […] the penetration of the future into time. The Eucharist is entirely live, an d utterly new; there is no element of the past about it. The Eucharist is the incarnation live, the crucifixion live, the resurrection live, the ascension live, the Lord’s coming again and the day of judgment, live. […] ‘Now is the judgment of the world’ (John 12:31). This ‘now’ of the Fourth Gospel refers to the Eucharist, in which all these events represent themselves immediately to us, without any gaps of history between them'[16]

Giotto, Crucifixion, Capella degli Scovegni, Padua

Giotto, Universal Judgment

It is undoubtedly the primacy of the theme of judgment which is the most intentionally troubling aspect of Gubaidulina’s Passion setting. Although, in accordance with Eastern Christian tradition, she emphasizes that the Cross can only be understood in the light of the Resurrection (significantly sketching St John Easter before embarking on the Passion), she makes no attempt to mitigate a general atmosphere of metaphysical dread, which is heightened by the passages from the Book of Revelation. Between the vertical and horizontal dimensions of the piece, Gubaidulina somewhat cryptically remarks,’ runs the double helix of advocacy and accusal'[17]. Fathoming what she means by this is not straightforward, but it would seem that her theological intention is to communicate that God in Christ (as implied by her emphasis of the Logos-God unity stated in John 1:1) is somehow – incomprehensibly from a human point of view – simultaneously the world’s judge and advocate, since it is humanity’s accuser, the Devil, who is ‘thrown down’ (as Gubaidulina has the soprano sing in the ninth section entitled ‘A Woman Clothed with the Sun’), conquered by the blood of the Lamb.

Here we are confronted by a disturbing ambiguity in the composer’s thought; on one level, her quotation of the words ‘for the devil has come down to you with great wrath’ (Rev. 12) might be taken as an indication that the terrifying violence of sections of the St John Passion such as the opening of the seven seals in the sixth movement is not divine in origin. On the other hand, it is clear from the work’s climactic eleventh movement, ‘The Seven Bowls of Wrath’, that Gubaidulina also wants to emphasize the future outpouring of God’s anger against humanity. This ending, in which visceral dramatic impact and a sense of (dark) mystery prevail against a sense of false closure or premature reconciliation, is as surprising as it is unnerving:

‘I sensed that the narration of Jesus’s earthly life path must in no case be allowed to end with a “solution of the dramatic conflict;” after such a dramatic process, there could only be one thing – a sign from the Day of Judgement. This meant an extreme dissonance, a kind of cry or scream. And following this final scream, only one thing was possible – silence. There is no continuation and there can be no continuation: “It is finished.”[18]

It is evident that Gubaidulina’s use of the Book of Revelation at this point derives from her apocalyptic view of the contemporary world as much as from a reading of the Passion narrative itself. Although I have tried to suggest a Christological rationale for her importing of the words of the Johannine apocalypse, the impression left by her St John Passion is not that she is interpreting the visions of Patmos as simply a fully-realized symbolization of Christ’s suffering. Instead Gubaidulina is prophetically insistent that herein lies the fate of the world. Defending her decision to conclude with the ‘Seven Bowls of Wrath’ in an interview in 2001, Gubaidulina explained that she regarded the oratorio’s finale as a personal ‘answer to Ivan Karamazov’ (presumably meaning his famous rejection of the idea that a ‘higher harmony’ in a future existence could somehow justify the suffering of the innocent in this one). For her it is evident that ‘man should have to experience divine wrath for having chosen evil instead of good’ and that the message of John about the primacy of the will of the Father is crucial in our times when the world is ‘on the verge of extinction'[19]

The apparent bleakness of the message of this work, like that of other post-Soviet choral masterpieces such as Arvo Pärt’s Kanon Pokojanen or Alfred Schnittke’s Psalms of Repentance, is no doubt unfashionable. The fact that Gubaidulina’s Passion setting has so far received very little by way of critical reaction to her theology seems to me to be indicative of a certain unwillingness to face up to its challenging content; indeed it might be argued that it has been best understood by those critics who have taken offence to it, rather than by those who have paid lip service to its purely aesthetic qualities while evading the thorny moral and spiritual issues it raises. I would certainly like to know whether I am not the only one to feel that substantial works of contemporary art such as Gubaidulina’s are seeking and merit a deeper level of substantive discussion than they tend to receive at the hands of critical opinion which largely views music in terms of the realization of career rather than as the expression of a higher imperative. In listening to Gubaidulina’s St John Passion it seems obvious that we have exceeded the boundaries of mere aesthetics. We are rather confronted by the scream of Golgotha which we would rather avoid, but which we must face in our lives if we are to progress beyond religious sentimentality to genuine faith.

There is no doubt that composing from a perspective of post-Easter hope without neutralizing the horror of Good Friday represents an extremely difficult task with which all modern composers from Penderecki to James MacMillan have had to wrestle. In a candid and as far as I can see untranslated Russian interview from November 2000, Gubaidulina expressed her reservations about the other three Passion 2000 works commissioned by the Stuttgart Bachakademie in terms of their approach to the problem:

‘The first one [Wolfgang Rihm] doubts, a second amuses himself [Osvaldo Golijov], a third wants to re-invent everything anew [Tan Dun]. And to all, except for me, it seems that the reaction to the crucifixion of Christ should be one of rejoicing and well-being. There you have it – the end of the 20th century and the beginning of the 21st. From my standpoint that’s frightening.'[20]

What is frightening to Gubaidulina is the sense of false security (which she finds expressed in Rihm’s Deus Passus) contained in the idea that Christ’s suffering in our place has annulled the reality of approaching Divine Judgment; her St John Passion is a deliberate attempt to dispel what she sees as such false consciousness.

Whether Gubaidulina has overstated the case in her Passion in her concern to emphasize the contemporary relevance of the theme of divine judgment is a matter for debate. Maybe I am simply being squeamish, but at times it is difficult not to feel that the terror is so unremitting in the work that even the entirety of the St John Easter is unable to counterbalance it, despite the ecstasy of its peroration ‘I saw a New Heaven and a New Earth’. This is perhaps partly a question of harmonic/melodic idiom, in that the relative weight accorded to chromatic and diatonic passages is skewed so heavily in favour of the former that Gubaidulina’s music never attains the harmonious clarity of, say Arvo Pärt [21]. This is not merely a technical issue, however, as it seems to stem from Gubaidulina’s overriding theological concept. In her ‘double helix’ running between heaven and earth, ‘accusal’ of humanity seems to take aural precedence over ‘advocacy’ for humanity. Although the concept of the Logos as uniting the human and divine certainly provides the overarching textual framework to the piece, it is hard to avoid the impression of at least a residual polarity between the human realm and an inscrutable, vengeful divinity which is only nominally reconciled by the God-Man Jesus Christ. There are hints of this in other places in Gubaidulina’s output; for example, in the work In Croce written back in 1979, Gubaidulina had conceived the organ part, in contrast to the warm humanity of the ‘cello, in terms of ‘a mighty spirit that sometimes descends to earth to vent its wrath'[22]. Something similar can be felt in her Seven Words or in the furious organ clusters in the finale to the St John Passion, and the thematic concept begs some worrying questions. Is this ‘mighty spirit’ divine or diabolical? If it is indeed God the Father who is being symbolized by the organ, is there some threatening kind of commingling of light and darkness in Gubaidulina’s musical (if not theological) concept of the Godhead?

Questions such as these make listening to Gubaidulina’s St John Passion a fascinating but deeply disturbing experience. Nonetheless, whatever one may think of Gubaidulina’s verdict on her peers and her own apocalyptic reading of the Gospel narrative, her point regarding the need to take in the full measure of the crucifixion without spiritual complacency is well-taken. The central message of her gripping work is surely a valid and urgent one; the joy of Easter Sunday cannot be be authentically experienced if we are not prepared first of all to look seriously at our world – and at ourselves – with a sobering measure of fear and trembling.

___________________________________

NOTES

[1] McBurney writes of the striking “poverty” of the surface of Gubaidulina’s music, the way she generates enormous energy and concentration using the frailest wisps of sound, breath-like sighs and moans, scraps of Russian Orthodox chant, gigantic but extremely simple unisons, shudders and tremblings like the merest moments of tension from a film score, the simplest common chords.‘ Gerald McBurney, ‘It pays to be poor’, The Guardian, August 12, 2005, available on-line at http://www.guardian.co.uk/music/2005/aug/12/classicalmusicandopera.proms20051

[2] See David Fanning’s review for the International Record Review reprinted at https://ecmrecords.com/Press_Reactions/New_Series/1700/Pressreaction_1776.php

[3] Valentina Kholopova and Enzo Restagno, Sofia Gubaidulina: Zhizn’ piamiati [A life in memory] (Moscow: research monograph, 1996), 79-80, quoted in Michael Kurtz, Sofia Gubaidulina: a Biography (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2007), 149.

[4] Quoted in E.J. Tinsley, ‘Kenosis’ in Gordon S. Wakefield, ed. The Westminster Dictionary of Christian Spirituality (Philadelphia: Westminster Press, 1983), 238.

[5] Nikolai Berdyaev, Dream and Reality, 210, quoted in Carnegie Samuel Calian,The significance of eschatology in the thoughts of Nicolas Berdyaev (Leiden: Brill, 1965), 63n.

[6] The theological idea that the Divine act of creation itself should be seen kenotically, particularly developed in a Western context in the work of Hans Urs von Balthasar and Jürgen Moltmann (whose Trinity and the Kingdom of God draws significantly on Berdyaev), has become a key concept for many thinkers involved in the faith-science dialogue such as John Polkinghorne.

[7] Quoted in Kurtz, Sofia Gubaidulina, 149.

[8] Ibid., 150.

[9] Ibid..

[10] Vera Lukomsky and Sofia Gubaidulina, “My Desire Is Always to Rebel, to Swim against the Stream” in Perspectives of New Music, Vol 36/1 (Winter, 1998), 5-41:27.

[11] CD booklet to Hänssler Classic 98289 (September 2007), 64.

[12] International Bach Academy Stuttgart Passion 2000 brochure, quoted in Kurtz, 249. Again, there is a correspondence between Gubaidulina’s compilation of her libretto and the prophetic, eschatological dimension that Berdyaev sees in genuine creativity, ‘an upward flight towards a different world’, which in some way ‘signifies an ek-stasis, a breaking through to eternity.’ In opposition to what Berdyaev calls ‘symbolic’ creativity (‘to take symbols for reality is one of the chief temptations of human life’) which restricts itself to the realm of phenomena, he boldly posits the existence of ‘realistic’ creativity, which ‘would, in fact, bring about a transfiguration and the end of this world, and the emergence of a new heaven and a new earth.’ Artistic activity in this finite world inevitably falls back into the first type, but is fired by this ‘realistic’ creativity capable of genuine transformation of the cosmos, of which it provides us with a glimpse. ‘The creative act, alike in its power and impotence, is eschatological – a prefiguration of the end of the world.’ (Dream and Reality, 209). See Carnegie Samuel Calian, The significance of eschatology in the thoughts of Nicolas Berdyaev, 57-67 and Kurtz, Sofia Guabidulina, 105.

[13] It should be stressed that although Gubaidulina does at times criticize Western theological categories, her aim with the Passion was to go beyond the East-West divide (it is significant that she should, like Arvo Pärt, have found particular inspiration in Italian sacred art):

“The chasm between the two systems of faith saddens me deeply. The early Christians did not have such a chasm in mind. Jesus lives in our hearts, not in dogmatic systems. That’s why I decided to write a work that transcends divisions over dogma” (quoted in Kurtz, 250).

[14] Quoted in Sikorski – Magazine 01/10, published on-line at http://media.sikorski.de/media/files/1/13/27/4011/sikorski_magazine_01_10.pdf

[15] Quoted in Kurtz, 250.

[16] John D. Zizioulas, ed. Douglas Knight, Lectures in Christian Dogmatics (London: Continuum, 2008), 155.

[17] CD booklet to Hänssler Classic 98289, 64.

[18] http://www.sikorski.de/3028/en/sofia_gubaidulina_passion_and_resurrection_of_jesus_christ.html

[19] ‘По существу это мой ответ Ивану Карамазову. Человек должен пережить гнев Божий за то, что он выбирает зло вместо добра. Он должен это пережить. Вот моя концепция. […] Но эта версия для меня дорога – закончить именно гневом Божиим. Особенно сейчас, в этом веке это настолько актуально. Именно в тексте Иоанна, который настаивает на том, что самое главное – это воля Отца, заключена судьба всего мира, который сейчас на грани исчезновения. Мне кажется, что именно это Евангелие и Апокалипсис сейчас наиболее актуальны…’ (Interview for Deutsche Welle, 20.10.2001) http://www.dw-world.de/dw/article/0,,340677,00.html

[20] ‘Один сомневается, другой играет, третий хочет осмыслить все по-новому, и всем им, кроме меня, кажется, что реакцией на распятие Христа должны быть веселье и благополучие. Вот это — конец ХХ и начало XXI века. С моей точки зрения, это страшно.’ (Газета “Коммерсантъ”, №207 (2092), 03.11.2000, reprinted online at http://www.kommersant.ru/doc/162447). It should be said that elsewhere in the interview Gubaidulina does however acknowledge Rihm’s seriousness of purpose. Her assertion that he treats Christ’s suffering as finished business would seem difficult to uphold in the face of Rihm’s use of Paul Celan’s Tenebrae to conclude his Deus Passus, an ending which in its way is just as disconcerting as the ‘Seven Bowls’ in Gubaidulina’s work.

[21] To some extent the two composers can be said to represent two constrasting strands of Eastern Orthodox thought – Gubaidulina being closer to the religious philosophy of Berdyaev and the ‘sophiology’ of Soloviev and Bulgakov, Pärt to the ‘neo-patristic’ school and the monasticism of Mt Athos.

[22] Quoted in ‘The Fire and the Rose’, Louth Contemporary Music Society/Drogheda Arts Festival programme booklet, May 1, 2010, available on-line at http://issuu.com/exquinn/docs/sofia_programme__proo