(Thoughts for Rachel Held Evans, Tony Jones and Tim Challies)

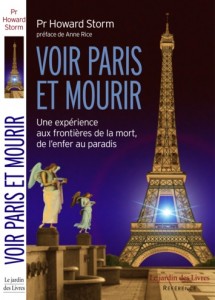

Again, an embarrassingly long time has passed since the last instalment of this particular thread on near-death experiences, at the end of which we left NDEr Howard Storm languishing in the ‘sewer of the universe’ following his (shambolic) hospitalization at the Cochin hospital in Paris with a ruptured duodenum in 1985.

This is not of course to say that the subject has gone away in the meantime. In particular, there have been at least three heated discussions of the topic in the theo-blogosphere (focussing on Baptist pastor Don Piper’s best-selling 90 minutes in Heaven) hosted by Tim Challies at http://www.challies.com/articles/heaven-tourism, Rachel Held Evans http://rachelheldevans.com/afterlife-memoirs , and Tony Jones at http://www.patheos.com/blogs/tonyjones/2012/06/22/don-piper-did-not-go-to-heaven/#comments .

The many readers’ reactions on these pages are perhaps just as if not more interesting than the original articles of the three bloggers in question. Not least because of the participation of a fair number of near-death experiencers for whom the various objections raised by the sceptics (largely on theological grounds) do not square with the self-authenticating nature of what is evidently experientially compelling for them. A common and frustrating feature of the comments (with a few notable exceptions) is however the generally poor level of logical analysis, frequent recourse to a priori arguments and above all a lack of sober engagement with the substantial body of scientific research on the subject, much of which is readily available to the general public via the internet. I will return to all this at the end of the current article, but let’s begin with a very brief summary of the next stage in Howard Storm’s gripping narrative in My Descent into Death.

The story so far: Storm, having been left untreated on a hospital trolley for 10 hours in a life-threatening condition, has had an unexpected out-of-body experience, during which he has been duped into following a group of people dressed as hospital orderlies who lead him outside our normal realm of space-time and turn on him like a lynch mob. He has been able to repel his assailants by reciting something vaguely resembling a prayer, but now finds himself in total existential isolation, ‘left alone to become a creature of the dark’. Storm (who despite his professed atheism had been brought up attending a Congregational church on the outskirts of Boston) then recalls himself as a small boy ‘full of innocence, trust, and hope’ singing ‘Jesus loves me, da da da’:

‘A ray of hope began to dawn in me, a belief that there really was something greater out there. For the first time in my adult life I wanted it to be true that Jesus loved me. I didn’t know how to express what I wanted and needed, but with every bit of my last ounce of strength, I yelled out into the darkness, “Jesus, save me.”‘[1]

This is the one part of Storm’s story that in isolation might at first sound suspiciously like a piece of traditional Christian apologetics; at this point, there appears a light ‘brighter than the sun, brighter than a flash of lightning’, and a Being of Light (identified as Jesus in the book) radiating unconditional love, who rescues him from the cosmic cesspit.

The Being of Light takes Howard Storm up and out of the darkness towards the ‘brilliant white center of the universe’. However, Storm (whose tone throughout is remarkably free from self-exaltation) describes himself as racked by feelings of shame, thinking to himself “I am scum that belongs back down in the sewer. They have made a terrible mistake. I don’t belong here.” At this point, he is reassured that “we don’t make mistakes, and you do belong here”, and is comforted by the appearance of beings whom he depicts in terms that could have been taken straight from Olivier Messiaen’s commentaries to works such as Quatuor pour la fin du temps or Couleurs de la cité céleste:

‘Then Jesus called out in a musical tone to some of the luminous entities radiating from the great center. Several came and circled round us. The radiance emanating from them contained exquisite colors of a range and intensity far exceeding anything I had seen before. It was like looking at the iridescence in the deep brilliance of a diamond. We simply do not have the words to express their beauty. When you look into a bright light, the intensity hurts your eyes. These being were far brighter than the most powerful searchlight, yet I could look at them with no sense of discomfort. In fact, their radiance penetrated me; I could feel it inside and through me, and it made me feel wonderful. It was ecstasy. These were the saints and angels.'[2]

Fra Angelico (1395/1400-1455), Annunciation (detail), Museo San Marco, Florence

(Messiaen’s inspiration for the costume of the Angel in the première of Saint François d’Assise)

Light untellable

Such descriptions of an unearthly radiance shining from within, incomparably brighter than any created light, yet curiously possible to contemplate without being blinded, are so common and similar within the near-death literature as to have become a cliché. However, it should be stressed that they seem to occur irrespective of the religious background (or lack of it) of the experiencer, and join a long mystical tradition, as Evelyn Underhill points out in her 1911 classic Mysticism:

“Light rare, untellable!” said Whitman. “The flowing light of the Godhead,” said Mechthild of Magdeburg, trying to describe what it was that made the difference between her universe and that of normal men. “Lux vivens dicit” [the living light speaks], said St. Hildegarde of her revelations, which she described as appearing in a special light, more brilliant than the brightness round the sun. It is an “infused brightness,” says St. Teresa, “a light which knows no night; but rather, as it is always light, nothing ever disturbs it”[3]

The language employed to evoke the notion of a light unknown in worldly categories is arrestingly similar in many contemporary near-death reports, however much they may diverge in the metaphysical interpretation of the radiance:

‘It looked unspeakably bright, as if it was the centre of the universe, the source of all light and power. It was more brilliant than the sun, more radiant than any diamond, brighter than a laser beam light. Yet you could look right into it.’ (A Glimpse of Eternity: One Man’s Encounter with Life Beyond Death, Ian McCormack/Jenny Sharkey. Available on-line at http://aglimpseofeternity.org/ians-testimony/ians-testimony.php)

‘All of a sudden, I was aware of a tiny bright light far away in the “sky” but rapidly coming nearer and nearer. It was shaped like a ball and it was indescribably bright. I tried to shade my eyes, but I did not need to. Despite its incredible brightness and brilliance, it did not dazzle me a bit!

Presently, this light stopped at a distance right above me. It was a sun about the same size as the sun of our world, but it was indescribably brighter. I kept staring at this sun wondering how a light could possess such brilliance.’ http://near-death.com/wagner.html

‘It was like a hundred thousand suns. Bright, incredibly bright. I could look directly in that light. It was so very powerful and ever so bright.’ http://celestial.kuriakon00.com/nde/ken_mullens.htm

‘The pinpoint of Light became a brilliant white beam a trillion times brighter than the brightest sun imaginable, and began to move toward me. At first, it appeared to be bands of multifaceted light being stretched and pulled together. I knew this Light was the presence of God.

I was awestruck, overwhelmed by the Light, the love, the love of God for me! I knew I could go into this Light, which was part of a tremendous force. And, although the Light was brighter than a thousand suns, it didn’t hurt my eyes.’ http://www.near-death.com/morrissey.html

‘I looked at the fire and realized it was brighter than a thousand suns but you could stare at it without hurting your eyes.’ http://iands.org/experiences/nde-accounts/809-kissed-by-a-marshmallow.html

‘The light – the fantastic light. It was brighter than the sun shining on a field of snow. Yet I could look at it and it didn’t hurt my eyes.’ http://www.near-death.com/group.html

‘The light was so bright that it was brighter than 10,000 suns and I immediately said, “This should be burning my retinas, but it wasn’t. It was a gentle but powerful light. It was pulling me like a gentle magnet.’ http://www.in5d.com/spiritual-reality-nde.html

‘Then I saw a great white light at the end of the tunnel and to me this light was God. I don’t know how to explain it other than it was brighter than the sun.’ http://iands.org/nde-stories/nde-like-accounts/371-light-brighter-than-the-sun.html

‘We then began going towards this beautiful light. As we got closer to it, the light just engulfed me. It was brighter than the sun but didn’t hurt my eyes.’ http://www.examiner.com/article/glauco-schaffer-and-his-two-brothers-drowning-ndes-ii

In the company of the beings of Light Howard Storm proceeds to undergo what is one of the most striking features of many near-death accounts, and an aspect for which no physiological account of the NDE phenomenon (as for example produced by a lack of oxygen, an excess of CO2 in the blood, endorphin action or the administration of anaesthetics such as Ketamine) has ever produced a coherent explanation: a panoramic, interactive life review.

While by no means a universal part of near-death experience reports, the similarities between life reviews in the NDE literature are such as to merit serious comment. The idea that in the last moments before death the dying person sees her whole life flash before her in an instant is such a commonplace as to be the stuff of urban legend, but the type of life review described by Storm and many others is much more than this. Moreover, these reviews are often intriguingly counter-intuitive, even for those of us brought up in religious traditions in which the inexorability of judgment is an integral part of the structure of moral accountability built into the universe.

Although researchers have stressed that there is a wide variety amongst reported life reviews, there are at least three consistent features of accounts such as Storm’s which are striking for the way in which they confound pre-conceived notions and can be found recurring in many independent narratives:

i) The only dimension of human life which seems to be concerned is the question of how the near-death experiencer has treated other people while on earth. Society’s notions of ‘achievement’ seem to be entirely irrelevant; indeed, the life review may concentrate on events which at first sight seem completely trivial[4]

ii) Although initiated and accompanied by the Being or beings of light, the ‘judgment’ (which is probably best understood as preliminary and pedagogical, not a final verdict as in Biblical passages such as Matthew 25 or Revelation 20[5]) is basically a self-evaluation, a realization of the true moral import of our lives once we are taken outside our limited individual perspective.

iii) The key feature of the life review – and one whose very strangeness would seem to be an indication of authenticity – is that the reviewer is made to understand the effects of her actions on others from their point of view:

‘We watched and experienced episodes that were from the point of view of a third party. The scenes they showed me were often of incidents I had forgotten. They showed their effects on people’s lives, of which I’d had no previous knowledge. They reported the thoughts and feelings of people I had interacted with, which I had been unaware of at the time.'[6]

Another excellent example of this can be found in the account of Steven Fanning read out in Huston Smith’s thought-provoking Ingersoll Lecture given at Harvard Divinity School on October 18, 2001 entitled ‘Intimations of Mortality: Three Case Studies’:

‘With the Being beside me, exuding love and comfort to me, I re-experienced my life, and it was not what I would have expected. While growing up in a fundamentalist church, I had been told many times about what it would be like when one faced God after death. It would be something like watching God’s movie of your life (as in Albert Brooks’s film Defending Your Life). You would watch all the scenes of your life on the screen and there would be nothing you could do but admit that the record was true: ‘Well, I guess you got me, fair and square.’ But this is not what happened. It was a re-experiencing of my life, but from three different perspectives simultaneously.'[7]

Fanning describes the first perspective in terms of ‘reliving of overt events as it was re-experiencing the emotions, feelings, and thoughts of my life. Here were the emotions that I had felt and why I had believed that I had them. Here were my conscious reasons for the actions that I had taken. Here were the hurts I felt and my responses to them. Here was my emotional life as I recalled having experienced it.’ However, the second perspective is that of others:

‘I felt what they felt, I lived their emotions as they acted with and reacted to me. This was their version of my life. When I thought they were clearly out of line and reacted with anger or thoughtlessness, I felt the pain and frustration my actions caused them. It was an absolutely different view of my life and it was not a pretty one. It was shocking to feel the pain that another person felt due to what I had done even as, when I did them, I believed myself to have been fully justified because of the person’s own actions. At the time I had told myself that I was justified, but even if that were true, their pain was real. It hurt.'[8]

Many other similar examples of what eminent near-death researchers Kenneth Ring of the University of Connecticut and Evelyn Elsaesser Valarino aptly term a ‘surprising empathic turnabout’ could be offered here, but one particularly compelling one can be found in the NDE account of Thomas Sawyer as recounted in Ring’s and Valarino’s Lessons from the Light. In his review Sawyer among other things re-experienced an altercation in which he had beaten up a pedestrian whose only offence was that he had almost collided with a pick-up truck that Sawyer had been driving:

‘Tom was forced to relive this scene, and like many others who have described their life reviews to me, he found himself doing so from a dual perspective. One part of himself, he said, seemed to be high up in a building overlooking the street from which perch he simply witnessed, like an elevated spectator, the fight taking place below. But another part of Tom was actually involved in the fight again. However, this time, in the life review, he found himself in the place of the other party, and experienced each distinct blow he had inflicted on this man — thirty-two in all, he said — before collapsing unconscious on the pavement.'[9]

The comment on such life reviews in Ring’s and Valarino’s book is worth quoting:

‘Perhaps the most obvious — and important — insight that is voiced, in one way or another, is that this exercise forces one to think about the meaning of the Golden Rule in an entirely new way. Most of us are accustomed to regard it mainly as a precept for moral action — “do unto others as you would be done to.” But in the light of these life review commentaries, the Golden Rule is much more than that — it is actually the way it works. In short, if these accounts in fact reveal to us what we experience at the point of death, then what we have done unto others is experienced as done unto ourselves. Familiar exhortations such as, “love your brother as yourself,” from this point of view are understood to mean that, in the life review, you yourself are the brother you have been urged to love. And this is no mere intellectual conviction or even a religious credo — it is an undeniable fact of your lived experience.‘[10]

Returning to Fanning’s report, it is however the third perspective which is the only one that can be labelled as true in an ultimate sense:

‘It was not my version, with my justifications. It was not that of the others in my life, with their versions of my life and their own justifications for their own actions, thoughts, and feelings. It was an unbiased view, free of the subjective and self-serving rationalizations that the others and I had used to support the countless acts of selfishness and lack of true love in our lives. To me it can only be described as God’s view of my life. It was what had really happened, the real motivations, the truth. Stripped away were my lies to myself that I actually believed, my self-justification, my preference to see myself always in the best light.'[11]

Although the examples of life reviews I have given are situated in a Western context, medical sociologist Allan Kellehear has recently adduced interesting anthropological evidence to suggest that life reviews are not only found in Anglo-European NDE reports. Two studies carried out in 1990 (of 197 Beijing residents) and 1992 (of 81 survivors of the 1976 Tangshan earthquake) also confirmed the occurrence of life reviews in Chinese contexts. The same appears to be true in India, where the form taken by such reviews is however different; Indian accounts apparently tend to take the form of a reading of the life record of the experiencer (in accordance with Hindu belief). In Thailand, life reviews are reported as occurring in the presence of supernatural beings (Yama, Lord of the Underworld, and his servants the Yamatoots. The life review does not however seem to be found in African, Native American, Australian Aboriginal or Pacific NDEs. Whether this should be attributed to the relatively small amounts of research in these areas or, as Kellehear thought-provokingly argues, to differing notions of the self and moral accountability in such cultures is a matter of conjecture (see Janice Holden, Bruce Greyson, Debbie James (eds), The Handbook of Near-Death Experiences: Thirty Years of Investigation, 139-141, 152-154).

Towards a possible interpretation

How then can we interpret the phenomenon of the NDE life review given both the overwhelming structural similarities between accounts on one hand and on the other a certain sense that the experience is not only subsequently expressed in the context of the experiencer’s cultural matrix but also ‘tailor-made’ to suit the individual in question? This would seem to require much more interrogation of the data, but the most credible model is perhaps one that involves the notion of the life review as a ‘feedback loop’ (a concept advanced by celebrated NDEr Mellen-Thomas Benedict) that reflects the experiencer’s subjectivity and cultural background. Such a model also however needs to allow for the possibility that the Divine may ‘accommodate’ itself to the experiential categories of the NDEr for the pedagogical purposes that seem to be an integral part of NDE accounts. In other words, the encounter with a Being of Light present during a life review is no mere ‘projection’ generated by an individual’s psychology, but neither do we seem to be talking about an ‘objectifiable’ free-standing reality which reveals itself in precisely the same way to all who encounter it.

In comparison with the serious work over several decades into near-death experience carried out by some of the researchers referenced above, the public discussions hosted by Rachel Held Evans and Tony Jones (both of whose blogs I admire more generally, I should add) on the subject of near-death experience reports have unfortunately proved depressingly if predictably superficial. To reduce the issue to whether Don Piper ‘really’ – whatever that is supposed to mean in relation to non-bodily consciousness – spent 90 minutes in heaven or whether Colton Burpo’s perhaps hastily-ridiculed vision of Jesus with a ‘rainbow horse’ in Heaven is for Real (of which the most balanced appraisal I have yet found has been penned by Bruce Epperly here) is ‘compatible with Scripture’ is to trivialize a subject with potentially huge implications for the way in which we perceive both science and spirituality.

I cannot help feeling that a more productive conversation might have ensued had the question under consideration been the role of the life review in NDE reports, which in the estimation of Jeffrey Long (whose recent Evidence of the After-Life constitutes the most ambitious survey of NDE accounts yet published), appears to be the element of the near-death experience with the greatest subsequent impact on the lives of survivors, ‘by far the greatest catalyst for change.'[12] It is also perhaps the most resistant to any kind of reductionist approach due to the richness of its informational and ethical dimension. Indeed, even if it could be conclusively demonstrated that, say, inter-ictal discharges in the hippocampus or amygdala are capable of generating hallucinations as coherent as a panoramic life review[13], this would in itself do nothing to explain the extraordinary empathic content and sense of compassionate judgment found in accounts such as that of Howard Storm. Experienced meaning is not something reducible to changes in brain states; it rather requires assessment on a different explanatory plane. To use a musical parallel, no evidence of an endorphin surge while composing would ‘explain’ the epiphanic dimension of the Adagio of the Ninth Symphony of Anton Bruckner (a real musical ‘near-death experience’ if ever there was one)[14]. Looking to understand neural correlates of transcendent experience is certainly a valid area of research, but to look to chemical causation to explicate an encounter with unconditional Divine love is simply to make a category mistake.

I would therefore invite those who have commented on RHE’s and TJ’s blogs, as well as to those who weighed in during the recent controversy over NDE research at http://www.salon.com between Mario Beauregard and PZ Myers, to read a few accounts of life reviews such as those of Howard Storm or Steven Fanning (the more the better, as the evidence starts to stack up after a while), and then tell me what they think is going on.

_________________________

NOTES

[1] Howard Storm, My Descent into Death: a Second Chance at Life (New York: Doubleday, 2006), 24.

[2] Ibid., 28.

[3] Evelyn Underhill, Mysticism: A Study of the Nature and Development of Man’s Spiritual Consciousness (Methuen, 1912), 299.

[4] In another re-telling of his story, Storm remarks: ‘My life was shown in a way that I had never thought of before. All of the things that I had worked to achieve, the recognition that I had worked for, in elementary school, in high school, in college, and in my career, they meant nothing in this setting.[…]I got to see when my sister had a bad night one night, how I went into her bedroom and put my arms around her. Not saying anything, I just lay there with my arms around her. As it turned out that experience was one of the biggest triumphs of my life.’ (reprinted on-line at http://familytreemaker.genealogy.com/users/v/o/n/Gottfried-H-Von-sponneck/FILE/0003page.html )

[5] Terence Nichols of the University of St Thomas concurs in his perceptive and balanced chapter on near-death experience in his recent Death and Afterlife: A Theological Introduction ‘How does this peculiar element of NDEs relate to the individual or the last judgment? Certainly it is not the last or final judgment, in which we seee our lives in the context of all of human history. Rather, it seems to be a foretaste or a preview of the individual judgment – it is a judgment by one’s own conscience, after all – but in the light of a loving being’ (Death and Afterlife: A Theological Introduction (Grand Rapids: Brazos, 2011), 201n.). An interesting Jewish interpretation of the life review in Talmudic categories can be found at http://www.innernet.org.il/article.php?aid=299

[6] Storm, My Descent into Death, 30.

[7] Huston Smith, ‘Intimations of Mortality: Three Case Studies’, Harvard Divinity School Bulletin, Winter 2001-2002, 12-16 (available online at http://www.theisticscience.org/spirituality/DivBull2002winter-Smith.pdf ).

[8] Ibid.. Dutch cardiologist Pim van Lommel, author of an important study of cardiac arrest patients in the Netherlands, describes the same phenomenon in non-religious terms: ‘All of life, from birth up until the present moment, can be relived as a spectator and as an actor. This makes it much more than a speeded-up film. People know their own and others’ past thoughts and feelings because they have a connection with the memories and emotions of others. During a life review people experience the effects of their thoughts, words, and actions on other people when they originally occurred, and they also get a sense of whether love has been shared or withheld’ (Pim van Lommel, Consciousness Beyond Life: the Science of the Near-Death Experience (New York: HarperOne, 2010), 35). The NDE literature abounds with such examples, e.g. Sandra Rogers (following a suicide attempt by gunshot in 1976): http://www.near-death.com/experiences/suicide03.html or David Oakford (after a drugs overdose in 1979): http://www.near-death.com/oakford.html

[9] Kenneth Ring and Evelyn Elsaesser-Valarino, Lessons from the Light: what we can learn from the near-death experience (Needham, MA: Moment Point Press, 2006), 157-8. Emphasis original. Sawyer’s own account of his life review, which does not include the incident related by Ring but does describe the review in terms of a similar triple perspective to that mentioned by Fanning, can be read at http://www.near-death.com/experiences/reincarnation03.html A further arresting life review not dissimilar to that of Howard Storm can be found in the case of another former atheist, Barbara Whitfield, http://www.aciste.org/index.php/integrationaccounts?id=71

[10] Ibid., 161-2. Emphasis original. Ring’s interpretation is close to that of British philosopher David Lorimer’s notion of ’empathetic resonance’, the conviction that the Golden Rule is not merely an ethical exhortation but an expression of the fundamental interconnectedness of all reality. See also Bruce Greyson, ‘Near-Death Experiences and Spirituality’ in Zygon, 41/2 (Summer 2006), 393-414:404. I have commented elsewhere on the way in which contemporary scientific work on mirror or ‘Gandhi’ neurons (V.S. Ramachandran) appears to be revealing that even in our corporeal existence we quite literally have the capacity to feel the pain of others. See Peter Bannister, ‘The Return of Spirit: Christian theology and consciousness research’, available online at www.peterjohnbannister.com/TheReturnofSpirit.pdf

[11] Huston Smith, ‘Intimations of Mortality’, 14.

[12] Jeffrey Long and Paul Perry, Evidence of the Afterlife: the Science of Near-Death Experiences (New York: HarperOne, 2010), 110.

[13] This is the suggestion made by Jason J. Braithwaite in the article ‘Towards a Cognitive Neuroscience of the Dying Brain. An in-depth analysis and critique of the survivalists’ neuroscience of near-death experience’ (Skeptic Magazine 21/2 (Summer 2008)).

[14] The choice of Bruckner for this illustration is deliberate; as the conductor Sergiu Celibidache remarked late in life, “To him, time is different than it is to other composers. To a normal man, time is what comes after the beginning. To Bruckner, time is what comes after the end. All his apotheotical finals, the hope for another world, the hope of being saved, of being again baptised in light, it exists nowhere else in the same manner”. Quoted in http://www.mtosmt.org/issues/mto.98.4.5/mto.98.4.5.james.html . Emphasis mine.