In the course of the last week much has been said and written about the Catholic Church’s newest saint (newest in a formal sense, as in the eyes of millions throughout the Catholic and non-Catholic world her sainthood was already a certainty at the time of her death in 1997), Mother Teresa of Calcutta. It was perhaps predictable that news outlets looking for sensation (goodness is boring, after all) would scour the horizon for dissenting voices, for example complaining about the lack of attention to issues of basic hygiene on the part of the Missionaries of Charity or accusing Mother Teresa of using her work as a pretext for proselytizing the population of Kolkata. The critics have however thankfully been in a distinct minority compared to those for whom the diminuitive Albanian nun from Skopje in a tangible sense epitomized God’s mercy in an all-too-often merciless 20th century.

Pope Francis’s homily for Mother Teresa’s canonization, which you can read here speaks for itself and I will not attempt to add anything to it. I would however like to make some brief comments relating to her profound and mysterious spiritual life as revealed in her writings, which have perhaps not occasioned as much comment as they deserve but are arguably no less significant for our society than the visible testimony of her practical work.

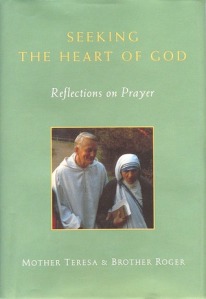

Above all else, St Teresa of Calcutta’s mission cannot be properly understood without grasping the essential unity of action and contemplation in her life, a distinguishing feature that she shared with another emblematic Christian witness of the twentieth-century, Frère Roger of Taizé (1915-2005), with whom she co-authored the books Mary, Mother of Reconciliations (1988) and Prayer: Seeking the Heart of God (1992). The rootedness of her work in the eternal rather than merely temporal perspective offered by Christian contemplation effectively constitutes the difference between action and mere activism ; failure to comprehend this difference lies at the heart of the misunderstanding of the fundamental purpose of her ‘homes for the dying’ by those whose frame of reference is primarily socio-political and whose yardstick by which to measure success is quantifiable results.

While stressing the importance of the contemplative dimension, it is important to emphasize that what makes the deep insights of Mother Teresa’s contemplative writings all the more remarkable is the fact that, as was only discovered after her death, they were written not in some kind of ecstatic rapture at God’s presence but rather in a state of spiritual aridity, even ‘darkness’, that seems to have lasted for decades. For example, Jesuit priest Albert Huart recalls how in 1985 Mother Teresa spoke to him bluntly about her sense of God’s absence:

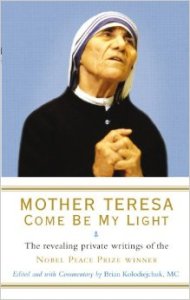

“Father, I do realize that when I open my mouth to speak to the sisters and to people about God and God’s work, it brings them light, joy and courage. But I get nothing of it. Inside it is all dark and feeling that I am totally cut off from God.” (Mother Teresa: Come Be My Light: The revealing private writings of the Nobel Peace Prize Winner (New York: Doubleday, 2007), 306.)

Such posthumous revelations of Mother Teresa’s inner state over a period of many years naturally came as a shock, even an affront to many who now viewed her as a hypocrite or even a plain atheist. This was however clearly not the case of her spiritual directors who were able to make sense of her often distressing interior experiences by pointing out their commonality with the path followed by some of the giants of Christian spirituality such as St John of the Cross.

As Brian Kolodiejchuk, director of the Mother Teresa Center and postulator for her beatification, writes in the introduction to the landmark publication Come Be My Light, Mother Teresa’s at times terrifying spiritual dryness is only comprehensible in the light of Tradition as

‘a sharing in the Passion of Christ on the Cross – with a particular emphasis on the thirst of Jesus as the mystery of His longing for the love and salvation of every human person. Eventually she recognized her mysterious suffering as an imprint of Christ’s Passion on her soul. She was living the mystery of Calvary – the Calvary of Jesus and the Calvary of the poor.’ (ibid., 3-4)

In this interpretation of thirst through the prism of the fifth of Christ’s Seven Last Words, there is a further link between St John of the Cross, Mother Teresa and Frère Roger of Taizé, who was especially fond of Jacques Berthier’s haunting musical setting of a Spanish text of Luis Rosales (1910-1992), De noche iremos, inspired by John of the Cross’s famous ‘Song of the soul which rests in the knowledge of God through faith’ (Cantar del alma que se huelga de conocer a Dios por fe). De noche iremos concludes with the enigmatic line ‘thirst is our only light’ (sólo la sed nos alumbra): it might be said that Mother Teresa’s life was a perfect illustration of this principle, in that the burning thirst for God, experienced in the dereliction of His absence, in a paradoxical sense became the driving force for her mission.

Here it is crucial to place Mother Teresa’s aridity in a broader context: Come Be My Light reveals that her years of inner darkness only ensued after intense purported mystical experiences in the 1940s as a Loreto nun. Evidence of these is presented in the book in the form of dialogue with Christ of a type familiar to students of Christian mysticism down through the centuries running from figures such as St Bridget of Sweden (1303-1373) or Thomas à Kempis (1380-1471) through to more modern examples such as the Polish nun Helena Faustyna Kowalska (1905-1938), Hungarian mother and factory worker Elizabeth Kindelmann (1913-1985) or French nurse, actress and playwright Gabrielle Bossis (1874-1950). Reading such material can be a somewhat disconcerting exercise for those who are shocked at the very notion of such dialogues, whose image of Jesus is edulcorated or sentimental, or who are offended by the unfashionable notion that Christ can make sacrificial demands of those wishing to follow him, yet robust conversations such as the following are absolutely typical of Christian mystical literature. Writing to Archbishop Ferdinand Perier of Calcutta in 1947, this is how Mother Teresa reconstructs one of her supposed dialogues with Jesus during prayer and Communion:

“Wilt thou refuse? When there was a question of thy soul I did not think of Myself but gave Myself freely for thee on the Cross and now what about thee? Wilt thou refuse? I want Indian nuns victims of My love, who would be Mary and Martha, who would be so very united to Me as to radiate My love on souls. I want free nuns covered with My poverty of the Cross. – I want obedient nuns covered with My obedience on the Cross. I want full of love nuns covered with My Charity of the Cross. – Wilt thou refuse to do this for Me?”

My own Jesus – what You ask it is beyond me – I can hardly understand half of the things You want – I am unworthy – I am sinful – I am weak. – Go Jesus and find a more worthy soul, a more generous one.

” You have become My Spouse for My love – you have come to India for Me. The thirst you had for souls brought you so far. – Are you afraid now to take one more step for your Spouse – for Me – for souls? Is your generosity grown cold? Am I a second to you? You did not die for souls – that is why you don’t care what happens to them. – Your heart was never drowned in sorrow as was My Mother’s. – We both gave our all for souls – and you? You are afraid, that you will lose your vocation – you will become a secular – you will be wanting in perseverance. No – your vocation is to love and suffer and save souls and by taking the step you will fulfill My Heart’s desire for you.” (ibid., 96-97)

What are we to make of such exchanges? Psychologists (as well as many contemporary theologians for whom this kind of bridal language and references to God’s desire for ‘victims of My love’ sit uneasily with ‘modern’ images of God) might of course be tempted to dismiss such dialogues as nothing more than interior monologues, the projection of internal conflicts – or repressed sexuality – in the language of an inherited religious vocabulary. The evidence of Mother Teresa’s unwavering lifelong response to what she perceived as God’s specific call to found what would become the Missionaries of Charity however suggests that such reductive interpretations, while undoubtedly fashionable in certain circles, are a little too convenient to do justice to the power of this material. And for many a reader, rational linguistic analysis can only take us so far when confronted by words such as those in italics. From the standpoint of faith, this is ultimately a Voice that you either recognize (cf. John 10:27) or don’t… but one which, once you do recognize it, you ignore at your peril…

With this comment on the limits of human language and interpretation, it seems appropriate to turn instead to music for two short tributes to St Teresa of Calcutta. Firstly, this miniature masterpiece of vocal imagination entitled A Drop in the Ocean by my friend Eriks Esenvalds (1977 – ) which I heard for the first time being sung to mesmerizing effect by the choir of Trinity College, Cambridge under Stephen Layton in 2011 while the highly talented young Latvian composer was in residence at the College. Written in 2006 and now a staple work for many choirs throughout the world interested in challenging but attractive contemporary repertoire, Esenvalds’ setting (here sung by the Latvian State Choir) combines the Our Father, a prayer of St Francis Assisi and some often-quoted words of Mother Teresa that have been a consolation to many on the point of succumbing to ‘compassion fatigue’ faced by the ills of the world:

‘My work is nothing but a drop in the ocean, but if I did not put that drop, the ocean would be one drop the less.’

The second tribute is the present author’s, a piece entitled Breathe in me (2013) setting a prayer to the Holy Spirit that I encountered through the Kolkata saint’s writings. Despite being frequently attributed to her, the words are actually those of St Augustine of Hippo, yet they remain intimately associated with Mother Teresa as she prayed them daily:

‘Breathe in me, O Holy Spirit, that my thoughts may all be holy. Act in me, O Holy Spirit, that my work, too, may be holy. Draw my heart, O Holy Spirit, that I love but what is holy. Strengthen me, O Holy Spirit, to defend all that is holy. Guard me, then, O Holy Spirit, that I always may be holy’ (quoted in Mother Teresa, A Call to Mercy: Hearts to Love, Hands to Serve , edited and with a preface and an introduction by Brian Kolodiejchuk, MC (New York: Image, 2016), 187).

Excellent piece, Peter. I’m going to share it on Facebook.

Please pray for Eric McDonald. Please pray for his salvation. Eric needs Jesus. Please pray God to open Eric’s eyes to his needs for Jesus Christ.

Please pray that God give Eric the grace to turn to Jesus Christ, repent, and be saved!!!

May God’s love fill his soul.