One of the periodic delights of living in Paris is the experience of showing visitors around this sometimes infuriating but undoubtedly stunning city. As with any great metropolis, it is all too easy to be made oblivious to Paris’s exceptional cultural richness by the daily routine of what is classically termed métro-boulot-dodo. Until, that is, you find yourself sharing the sights with those who are not so blasé about this incredible location for lovers of history and art. So it was with a properly renewed sense of wonder that we returned home after visiting two of Paris’s most astounding locations with family guests from the other side of the Eurotunnel .

The first was the renovated Musée d’Orsay, perhaps the world’s most concentrated collection of epoch-making visual art from the period 1848-1914; for anyone who knows even a little about the history of painting there is a sense of sheer overload in being in an enclosed space with so many masterpieces of figures such as Corot, Manet, Monet, Dégas, Cézanne, Renoir, Gauguin, Van Gogh …, any one of which would be the pièce de résistance in a lesser museum. It is not merely that the Orsay’s canvases are supremely beautiful in purely aesthetic terms, but also that each one carries rich human associations as a chronicle of the lived historical experience of an era. As the philosopher John D. Caputo (perhaps the foremost living Anglophone interpreter of what he terms the philosophical ‘witch-doctors’ of the Parisian rive gauche) likes to remark, something is ‘getting itself said’ through this art which goes beyond the purely personal vision of the artist.

To use another philosophical parallel, there is a sense when standing in front of the paintings in the Musée d’Orsay of what Jean-Luc Marion has famously called a ‘saturated phenomenon’, something which overwhelms our cognitive capacities by its excess, its sheer weight of what might be termed ‘radiance’ or ‘splendour’, to give a rough translation of the word Herrlichkeit which was so central to the thought of Jean-Luc Marion’s theological mentor Hans Urs von Balthasar.

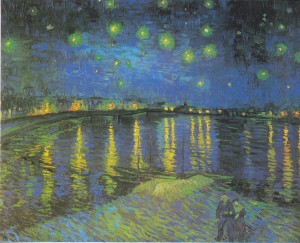

For me perhaps the best exemplification of this in the Orsay is Van Gogh’s unforgettable Nuit étoilée sur le Rhône, painted in Arles in 1888, which makes an impact when seen in the museum which is quite different from anything that can be conveyed by a reproduction of the picture. The sheer intensity of what one might call Van Gogh’s ‘meta-colours’ and the unbelievable thickness of the paint create the impression of what the Welsh 17th century poet Henry Vaughan famously described in his Night as a ‘deep and dazzling darkness’ which is more than simply physical and which evokes something akin to a state of mystical consciousness.

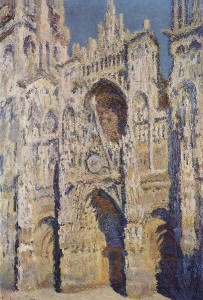

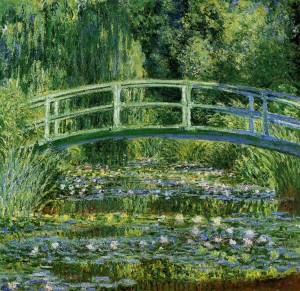

Our appreciation of a sense of the numinous within Van Gogh’s Provençal night sky is obviously bolstered by our biographical knowledge of the painter’s profound spirituality (which I already discussed in relation to Makoto Fujimura’s provocative reading of his other ‘Starry Night’ picture in my post ‘Fujimura’s Refracted Light’ ). Jean-Luc Marion’s notion of the ‘saturated phenomenon’ can however also be powerfully felt in wholly ‘secular’ pictures such as Monet’s light-drenched series of views of the Japanese bridge in the garden at Giverny. Interestingly, Marion himself, in his highly thought-provoking reflections on visual art published as La Croisée du visible, interprets Monet’s form of saturation in anti-metaphysical terms, as a reduction of painting to the data of immediate consciousness, excluding any other ‘object’, i.e. subject-matter. This is most apparent in his reading of Monet’s studies of the façade of Rouen Cathedral, in which the object is evidently not the cathedral but the play of light itself as experienced by the painter:

‘The portal of Rouen Cathedral does not appear differently lit during the course of the same day; on the contrary, even at high noon, it never stops disappearing; and less so by dazzlement (éblouissement) than by virtue of being all too perfectly recorded. To talk of dazzlement implies that one is constantly aiming at an object and therefore regrets that the excess of light prohibits a clear view, but here it is not a matter of seeing, through the excess of light, the intended object of a cathedral. It is about receiving this light itself, as perceived, in the place of and instead of any illuminated objective.'[1]

I can certainly understand Marion’s take on Monet’s Rouen series, in which it is additionally evident (a point so obvious that Marion does not even comment on it directly, although it reinforces his general interpretive line) that the whole spiritual significance of the Cathedral and the sculptures on its facade is of no interest to the painter whatsoever. Here the contrast between Monet and the symbolist school of French 19th century art is very striking in terms of the way in which the relationship between the visible and the invisible is approached; Marion defines impressionism’s fascination with light and shade as making the invisible (i.e. the medium of vision) visible at the expense of the object itself, which is effectively collapsed into the perception of the artist who is no longer trying to see anything ‘behind’ what is perceived by immediate consciousness. In other words, Marion claims that such painting does not point to anything beyond itself – Monet therefore both epitomizes and to some extent triggers modern art’s tendency to demolish any reference to a transcendent depth other than what is immediately perceptible. To this Marion opposes the Biblical and early Christian tradition of the icon, whose essence is to turn the viewer’s attention away from itself to its invisible prototype, the paradigmatic case being Christ as the eikon of God, the suffering servant of Isaiah 52-53 who allows himself to be disfigured in order to draw us to the Father.[2]

However, returning to Monet’s Japanese bridge, it could be argued that a somewhat different interpretation is also possible. In contrast to what are to my mind the predominantly technical, if impressive, explorations of the pointillists such as Seurat and Signac, Monet’s paintings should surely not be regarded as devoid of depth. I for one (albeit bringing my own world-view and prior experience with me to the Musée d’Orsay) would be more inclined to say that regardless of Monet’s own atheism, the saturation with light emanating from his canvases can strike the spectator as a powerful form of this-worldly transcendence endowed with its own sense of mystery and depth even if there is no reference to anything beyond an ‘immanent frame’, to use Charles Taylor’s useful term when discussing the historical process of secularization in Western culture. I can agree with Marion that the ‘medium of vision’ does take precedence over subject-matter, and symbolic reference is nowhere to be found, but there is still ‘dazzlement’ – as Marion himself admits – to the extent that light itself has been elevated to transcendent status. This is not a simple case of ‘disenchantment’, not a full-blown attack on transcendence per se such as can be found, say, in Manet’s coldly lit Olympia (as I discussed in relation to Jacques Ellul’s insightful interpretation of Manet in The Empire of Non-Sense ).[3]

__________________

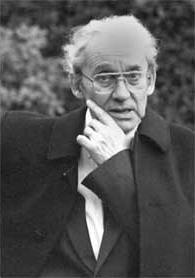

This concept of dazzlement/éblouissement , explored theologically in a manner very similar to that of Marion, also appears in the writings of the composer Olivier Messiaen. In a lecture given in Notre-Dame de Paris in December 1977 he uses it to convey his intuition of a link between colour and religious experience, referring to the second mythical location which we visited last weekend, the Sainte Chapelle built by Louis IX in the 13th century, of which I highly recommend taking a virtual tour that you can access by clicking here . Messiaen first encountered its iridescent windows when he was 10 years old, an experience which he describes as foundational –

‘What is going on in the stained glass of Bourges [Cathedral], the great windows of Chartres, in the rose windows of Notre-Dame de Paris and in the marvelous, incomparable stained-glass of the Sainte Chapelle? Firstly there is a host of figures, large and small, telling us the life of Christ, of the Blessed Virgin, the Prophets and the Saints: a sort of catechism in images. This catechism is enclosed in circles, heraldic shields, trefois; it obeys colour symbolism, it contrasts, superimposes, decorates, teaches, with a thousand intentions and a thousand details. Well, from far away, without binoculars, without ladders, without anything to aid our weak eyes, we see nothing: just a totally blue, green or purple stained-glass window. We don’t understand, we are dazzled.

‘God dazzles us with an excess of Truth’, says St Thomas Aquinas.'[4]

Messiaen goes so far as to describe his experience of dazzlement, which he closely links to the phenomenon of synaesthesia (the simultaneous perception of sound and colour), as a ‘breakthrough towards the beyond’ (‘percée vers l’au-delà’). The humbling of our senses and our understanding that we feel in the presence of overwhelming sensory beauty opens us, Messiaen contends, to the transcendent reality of God:

‘All these forms of dazzlement are a great lesson. They show us that God is above words, thoughts, concepts, above our earth and our sun, above the thousands of stars around us, above and outside time and space, all these things which are as it were attached to Him. […] And when musical painting, coloured music, sound-colour [le son-couleur] magnify him through dazzlement, they participate in the beautiful praise of the Gloria, saying to God and Christ: “You alone are Holy, You alone are the Most High!” On inaccessible heights. In so doing, they help us to live better, better to prepare our death, better to prepare our resurrection from the dead and the new life which awaits us. They are an excellent “passage-way”, an excellent “prelude” to the unsayable and the invisible.'[5]

Messiaen’s lecture concludes by an affirmation of hope in the Beatific Vision in the risen life, which will be ‘a perpetual dazzlement, an eternal music of colours, an eternal colour of musics’.[6]

_______________

Eight years after Messiaen made his remarks, an art professor named Howard Storm was visiting Paris with a group of his students from Northern Kentucky University. An atheist for whom the only contact with spirituality was his own artistic experience of the mysterious variability of ‘inspiration’ from one day to the next, he would later recall finding himself strangely overcome with emotion on seeing both the Sainte Chapelle and the Monet water-lilies in the Orangerie of the Tuileries gardens. However, on that 1985 trip Howard Storm would unexpectedly find himself undergoing a life-changing liminal experience (recounted in his book My Descent into Death: a Second Chance at Life) which, as we will see in the next portion of this post, would not only provide him with a stunning personal confirmation of Messiaen’s words in Notre-Dame de Paris concerning the ‘eternal music of colours’, but which is now regarded by many as one of the most dramatic near-death experiences in modern times …

NOTES

[1] Jean-Luc Marion, La Croisée du Visible (Paris: Presses Universitaires de France, 1996), 32. Translation mine.

[2] ‘The question can be formulated as follows: where, originally, can an image be found which divests itself of its own visibility in order to let another gaze break through it? The answer is clear: the Servant of Yahweh allows himself literally to be disfigured (to lose the visible splendour of his own face) in order to do the will of God (which only appears in his actions). The Servant sacrifices his face – he allows his ‘image’ to be unmade: ‘there were many who were appalled at him – his appearance was so disfigured … his form marred beyond human likeness’ (Isaiah 52:14; cf. Psalm 22:7). By effacing all glory from his own face to the point of obscuring his very humanity, the Servant allows nothing to be seen of him other than his acts, the latter resulting from obedience to the will of God and thus allowing it to be made manifest’ (ibid., 109. Translation mine).le

[3] The closest musical parallel to Monet in this respect is perhaps not Debussy, whose frequent association with ‘impressionism’ is misleading to the extent that it obscures his alignment with symbolist currents (particularly evident in Pelléas et Mélisande), but Frederick Delius, who lived in the French village of Grez-sur-Loing near Fontainebleau from 1897 to 1934 together with his German painter wife Jelka. Notoriously opposed to Christianity and an avowed disciple of Nietzsche, Delius’s music is provocatively anti-theistic but remains ‘spiritual’ in a similar fashion to the ‘transcendentalism’ of figures such as Walt Whitman, whose Leaves of Grass provided the text for Delius’s haunting Sea Drift (1903-4).

[4] Olivier Messiaen, Conférence de Notre-Dame (Paris: Leduc, 1978), 12. Translation mine.

[5] Ibid., 13.

[5] Ibid., 15.